Originally you worked in science, engineering, and technology – have you always been interested in food studies and what prompted you to dive in to studying it fulltime after your retirement?

Yes, absolutely. In fact, studying the principles and practices of Persian cookery has been a very serious secondary mission and activity for me for over 40 years. The genesis of my interest in the subject goes back to my early graduate school years while at Cornell University. During a trip to Chicago in the summer of 1979 to visit family members whom I had not seen for many years, one of them shared several handwritten heritage Persian recipes along with several baby food jars full of a variety of hard-to-find dry Persian cooking herbs.

Do you use any of your previous training or work experiences in your research on the principles and practice of Persian cookery?

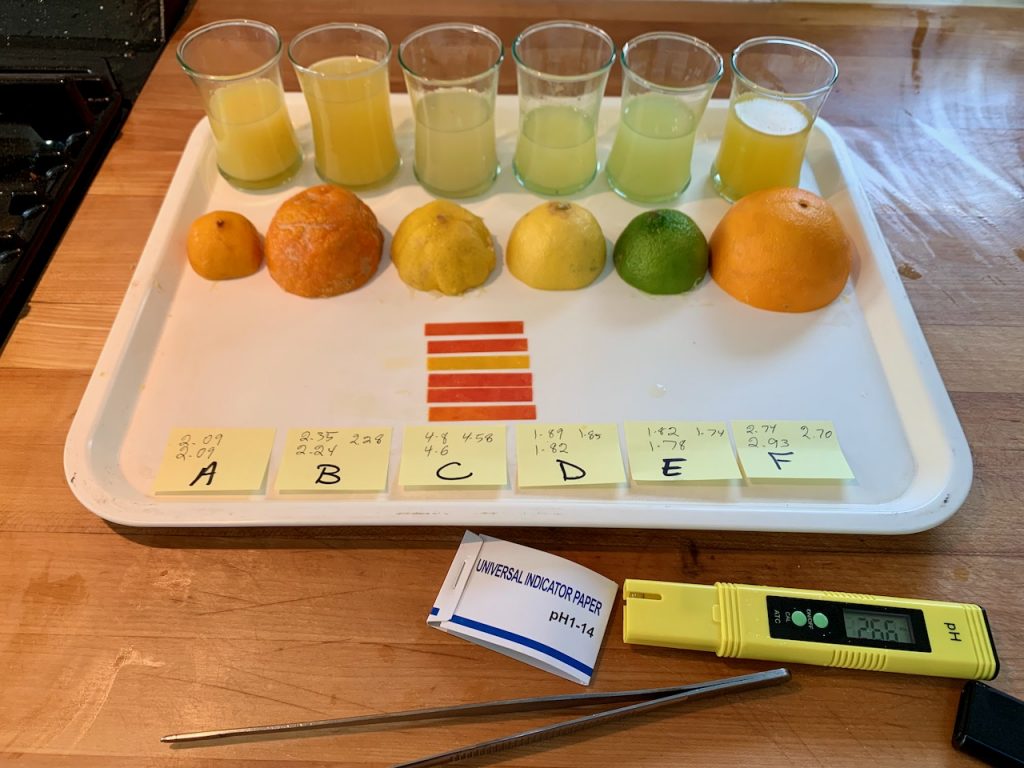

All the time. Utilizing a structured approach for exploring, researching, collaborating, planning, experimenting, testing, seeking feedback, learning, and documenting is a longtime habit developed during my graduate school years that I take full advantage of when doing my culinary related work. From studying historic Persian cookbooks and food-related manuscripts, it is very clear that the members of the Persianate society considered cooking both an art and a science. For example, a recently obtained handwritten cooking manuscript from 1800s, written in Persian language, has a title that translates to “The Science of Cooking Food, Making Drinks, Food Preservation and Food Pairing.”

In my opinion, such an approach is required to ensure that my to-be cookbook is comprised of well researched and accurate historical information, incorporates modern food science and food safety principles, its recipes are well tested, and the associated cooking methods are easily practiced in a modern western home kitchen.

Don’t get me wrong. I pay equal attention to the “art” component of cooking and cookery. The conceptual ideas and the creative imagination that human beings have and continue to contribute to gastronomy is as important.

I must, however, add that there is an equally important third dimension that I pay special attention to – the concept of Persian foodways. The story of Persian cookery is not complete if one does not consider economic, cultural, historical, social, and geographical aspects of it.

What advice do you have for people who may want to make a career or research interest change, especially those that are thinking of moving towards food studies?

For me, it has been more of a “priority change” than an “absolute change.” My formal academic training and professional experiences in engineering, science, and technology continues to be very close to my heart. The best way that I can explain is that getting deeply involved in food studies and cookery has been sort of a “calling” that had been whispering in my ear for over 40 years. I didn’t ignore the constant whisper, I listened to it, and nurtured the associated desire as a serious side hobby. And now, since retirement, it has been brought to the front burner with my full-time attention to it. My advice to others who might be hearing a similar whisper is to pay some attention to it on an ongoing basis, find ways to nurture and feed the underlying desire, until that time that you are ready to bring it to the front burner.

To demonstrate the idea, let me share a personal experience. As part of my professional life, I was fortunate to have a wonderful 20-year career at Lockheed Martin Corporation while living in Ithaca, NY – home of Cornell University. On the side, in addition to serving as an adjunct faculty at Cornell, I also served as an advisor to Cornell’s Undergraduate Iranian Student Association for several years. My wife and I used to host members of the Association and their families and friend to our home for various annual Iranian cultural celebrations. I would use those opportunities to nurture my strong desire for deeper and more serious culinary activities by investigating, learning (if necessary), and preparing a wide range of traditional Persian dishes for the Iranian student community at Cornell.

What drew you to join ASFS?

My interest in ASFS began a couple of years ago while experimenting with preparation of various Persian food items from different parts of a typical orange tree – including making jam from the petals of orange blossoms. During a casual conversation with a friend – a plant pathologist – I inquired about certain food study terminology for when all parts of a tree, throughout its annual lifecycle, are used for culinary purposes. She shared my inquiry with a member of ASFS whom in return posted it on the ASFS’s group emails. Within a span of a couple of days, over 30 individuals from across the world responded to my inquiry. The breadth, the depth, and the speed by which ASFS members responded was sufficient to convince me to join.

Could you tell us more about your research interests in the historical, cultural, and social practices of food preparation and consumption of the global Iranian diaspora community?

Any comprehensive discussion of “Persian Food” or “Persian Cookery” must include culinary principles and practices of not only those communities who live in the country that today is called Iran (including such ethnic groups as Kurds, Arabs, Azaris, Turks, etc.) but also certain long-term citizens of other parts of the world such as the Parsians of India (the Zoroastrian community that left Iran for India after Arab invasion), communities who speak Persian who are natives of countries other than Iran such as Afghanistan and Tajikistan, as well as the estimated 2 to 3 million Iranians living abroad who many of them migrated to other countries for a variety of reasons after the Iranian Revolution of 1979, i.e., the Iranian diaspora community.

What do you do as a Research Associate in the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences at the University of California, Davis?

Throughout my professional career, I have always had some formal associated with one or more academic institutions in such capacities as a visiting lecturer, or adjunct faculty, or chair of industry advisory committee, etc. It has been a rewarding life-long habit. After retirement, when my wife and I moved to Davis, CA, it was only natural to find ways to be associated with the academic community of the University of California, Davis. As a volunteer Research Associate in the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences at UCD, I do independent investigation of various aspects of Persian cookery and the associated topics, interact with others at UCD and other institutions around the world on topics of joint interest, and share results with the larger community through presentations and publications. I am much grateful for my associated with UCD.

You are working on a project about an innovative cookbook with historical information and modern food science techniques – can you tell us more?

Over the past 40 years that I have been studying Persian cookery, I have collected and carefully examined close to 100 Persian cookbooks written in different languages (primarily in Persian and English), published around the world (primarily in Iran, US, and UK), both historic cookbooks (published in 16th through 19th centuries) and contemporary cookbooks (published in 20th and 21st centuries). That experience has led me to envision a cookbook that would achieve several goals: (i) One that presents concise and well researched historical, social, cultural, geographical, and economical information about individual or groups of dishes (i.e., to be a foodways-centered cookbook); (ii) relevant modern food science and food safety imperatives are considered and described; (iii) methods are specifically designed for preparation in a typical modern home kitchen and all recipes will be tested in such setting; (iv) provides simple photographs of all dishes as through having been prepared by a typical Iranian home cook (i.e., without any food styling); (v) being a teaching cookbook in the sense that foundational dishes and foundational methods are detailed that once mastered can easily be tailored, adapted, and modified; (vi) incorporates not only the most important, famous, and popular dishes, but also dishes that are in the danger of being forgotten, regional dishes, historically significant dishes, and dishes of importance to various religions who have been present in Persianate society over the years (i.e., going above and beyond what one would find on the menu of a typical Persian restaurant in western world; (vii) serving the needs of a wide audience ranging from novice to experienced cooks, cooks with or without familiarity with Persian food, cooks with or without Persian heritage; and (viii) enabling the promotion and preservation of the heritage food items within the global Iranian diaspora community.

Several of your recent presentations and upcoming articles are about the Persian dish tahdig – what is tahdig, and why is it an important part of Persian cookery?

Tahdig is that delicious, buttery, golden, crunchy, round layer formed at the bottom of a Persian-style rice pot. (See Figures 1-3.) Literally translated, the Persian word tahdig means “bottom of the pot.” Some believe that it is the most coveted treat at a Persian meal and as such it is often referred by such phrases as the jewel of Persian cooking, the holy grail of Persian cooking, or the pièce de résistance of a Persian cook. It has been part of Persian cookery landscape for a long time – some of the earliest references to tahdig date back to the mid-1800s. Tahdig is often fought over by family members and guests during meals and disappears seconds after having been put on the table. Recently, tahdig has become much more than the crunchy layer of rice at the bottom of the pot. Persian cooks have introduced imaginative practices into the process of making tahdig. These creativities range anywhere from more efficient ways of cooking other elements of the meal (meat and vegetables) integrated with the tahdig in the bottom of the same pot, to using more pliable versions of tahdig as a bread substitute to make a range of sandwiches, to using the tahdig layer to create beautiful edible food art.

Do you have a favorite tahdig recipe that people can try making at home?

Tahdig is the direct byproduct of preparing the famous Persian-style rice called chelow which is very different from rice preparation methods in other cultures around the world. The classic process to make Persian-style rice involves long-grain rice going through the stages of being soaked in salted room-temperature water for several hours (optional), parboiled in salted water for several minutes, drained, poured back into the pot with butter on the bottom, and then slowly cooked over low heat for an hour, while covered tightly, during which the tahdig is formed at the bottom of the pot. For more information, see his article at Serious Eats: https://www.seriouseats.com/tahdig-persian-crunchy-rice-7187445

Recipe for Persian-Style Chelow Rice and the Resulting Tahdig:

Ingredients:

- White long-grain rice (e.g., Basmati): 3 cups

- Salt: 2 tablespoons

- Water: 8 cups

- Butter (or olive oil or other cooking oil): 4 tablespoons

Method (simplified):

- Place rice in a large bowl and wash with lukewarm tap water five times.

- Bring water and salt to hard boil in a large stockpot (don’t worry about the large amount of salt; most of it gets drained away).

- Add rice to the boiling salted water.

- Keep the heat high. Stir the rice a couple of times until the water comes to a hard boil again.

- Parboil the rice for about 8 minutes (or until al dente – test a rice grain; the center should still be a bit hard).

- Drain the cooked rice into a colander.

- Melt 4 tablespoons of butter (alternatively use olive oil or other cooking oil) into the now empty pot.

- Using a large, slotted spoon or a spatula, gently spread a one-inch-thick layer of parboiled rice from the colander into the bottom of the pot. Then slowly scoop the rest of the parboiled rice into the center of the pot, forming a rising pyramid-shaped pile of rice.

- Cover the pot very tightly (e.g., wrap the lid with a dish towel).

- Cook on low heat for about an hour. A layer delicious, buttery, golden, crunchy rice (i.e., tahdig) will form at the bottom of the pot.

- After the cooking is done, fill your sink with an inch of cold tap water. Put the pot in the pool of water – this will help in getting (peeling) the tahdig from the bottom of the pot. First scoop the rice that is sitting on top of the tahdig into a serving bowl. Once you get to the tahdig layer, use a large spoon or a spatula to peel the tahdig off of the bottom of the pot into a serving plate. Depending on the type of the pot used, it may or may not come out in one piece – not to worry, it will be delicious regardless.