In the second installation of our roundtable interview series, Member Spotlight coordinator Alanna Higgins talks pedagogy with Sonia Massari, Jonathan Deutsch, and Kerri LaCharite. Jonathan, Sonia, and Kerri tell Alanna about their approaches to teaching, how their teaching has evolved, and share some of the pedagogical resources they’re excited that they’ve recently come across.

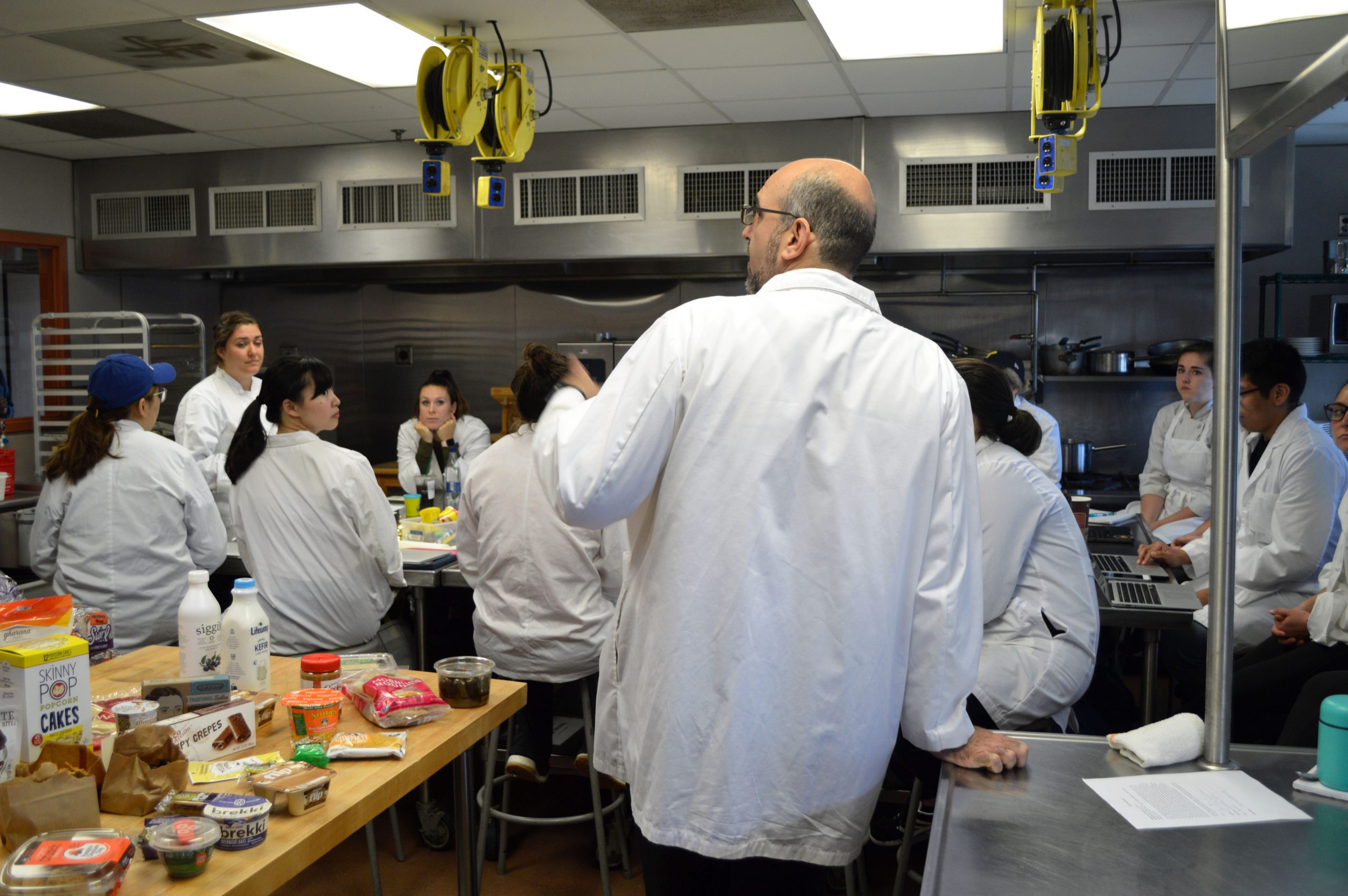

Dr. Jonathan Deutsch currently works as a Professor at Drexel University where he founded the Drexel Food Lab, a place for students and faculty to research sustainable, healthy, and accessible food systems. He was a James Beard Foundation Impact Fellow for leading a national curriculum around food waste reduction for culinary educators.

Dr. Kerri LaCharite currently works as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Nutrition and Food Studies at George Mason University. Her work draws from previous roles on several food policy councils and food banks, examining agriculture-based learning, sustainable food systems, and urban agriculture.

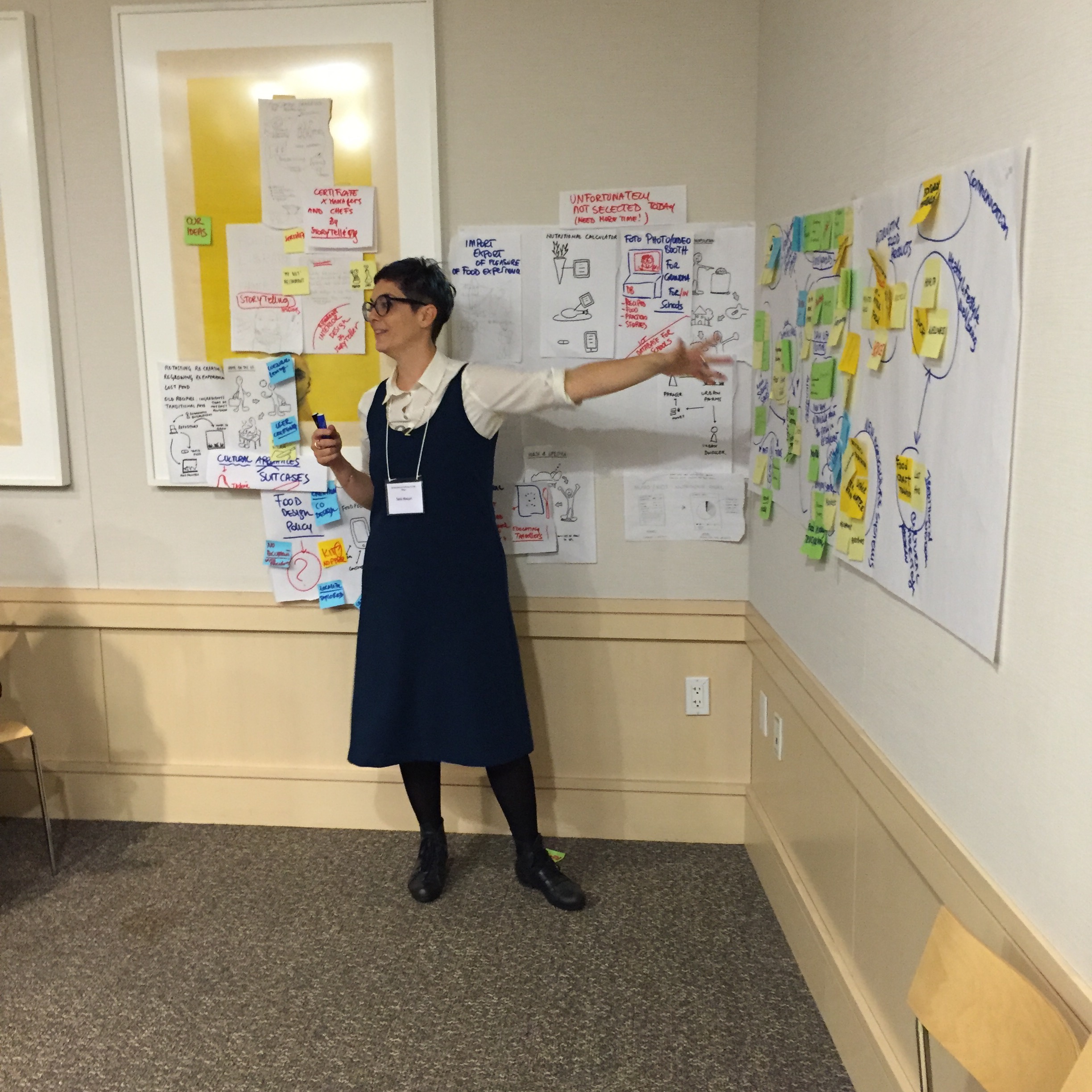

Dr. Sonia Massari currently teaches at several universities around Italy and has been a scientific consultant and senior researcher for the Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition since 2012. Dr. Massari has extensive experience designing and running study abroad programs for university students.

Could you tell us about the different classes you each teach?

Sonia: For 13 years I have been the academic director of the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign in Rome and therefore I have designed, developed and often also taught in their courses of food studies abroad (in particular in the courses of Food and Culture and Food and Media). I have designed more than 50 academic programs and 150 educational initiatives for US and international universities in my role as director of GLI. At the same time I have always taught graduate courses and specialized modules in many European universities: I teach a course in “Sustainability Design Thinking” at the University of Roma Tre and a course in “Sociology of Change / Design of emerging food scenarios” at the ISIA State School of Design. My modules on food design, new technologies and design thinking for the food sector have been included in the curricula of numerous universities: Gastronomic Sciences Pollenzo, SPD Master Food Design Milan, ESTHE Food Design Master / Portugal, SDGAcademy, UNESCO Food City Design Master Parma, Future Food Institute courses, to name a few. From Fall 2021 I joined the Future Food Institute group, as academic director of the Future Food Academy. In this role, I have had the opportunity to design and develop academic and innovative programs on the topics of food and sustainability.

Kerri: While my area of expertise is sustainability in food and agriculture, I teach a range of food classes within a Nutrition and Food Studies department from food systems and food security to cooking and an intro class to wine and beer. I really enjoy introducing students primarily focused on nutrition and health to concepts of sustainability and systems thinking, and how to work with food, which surprisingly I get many graduates and undergraduates who do not feel comfortable in a kitchen.

Jonathan: I am in a department of Food and Hospitality Management and an affiliate in our Department of Nutrition Sciences. Like Kerri, I teach the hands-on cooking classes for nutrition and food students, ranging from basic cooking to gastronomy. Like Sonia, I teach stakeholder-informed food product design for those students as well, which is also a big part of my research portfolio.

How do you choose the teaching methods you use and how you design your classes?

Sonia: First of all I try to understand the target. My way of teaching has the main purpose of helping students to see the world of food in a different way, from a different angle. Instead of showing them the problems and needs, I help them discover opportunities and find solutions. The design methods applied to the various stages of teaching are very useful. Furthermore, I always choose study and research methods that are close to the students’ needs and their competences: the use of media familiar to them, or storytelling techniques that are attractive to them, become paramount tools to engage and empower them. I love to create innovative educational paths, both experiential and challenge-based.

Jonathan: Sonia brings up an excellent point about keeping learning objectives and student needs in sight. If the content or assignments are not meeting students where they are, they won’t learn.

Kerri: I believe students learn more when they can take an active role in the learning. It keeps their attention, especially for three hour classes. Students get to experience concepts and practice skills in addition to it being more fun. I also don’t enjoy lecturing for any length of time. So, I try to incorporate experiential learning in every class. For classes like Fundamentals of Cooking that is easier. For other classes like Food Systems it is a little harder, and especially moving online. It takes a while to build up useful learning activities and experiences and what works in-person doesn’t necessarily translate online.

Jonathan: One of the big challenges, for nutrition majors in particular, is getting them to see the relevance of our classes to their profession. Our students are great, but unlike liberal arts students, are singularly focused on entering a specific profession. That is great because they are highly motivated but also frustrating in that I get questions like, “Why do I need to know about food systems to be a (chef, hotel manager, dietitian). Gah!” So I often focus on real world professional projects like designing a foodservice facility and menu for a real world challenge or working with sustainable and nutritious food products and making them appealing in a packaged snack.

Do you have a favorite teaching method or technique? If so, what is it and how do you use it in your classes?

Jonathan:

I like conflating lecture and lab. Learning “the theory” or content of the course through a hands-on kitchen based approach. It’s one thing to read Rachel Laudan’s “A Plea for Culinary Modernism” and discuss it, which we do. But it’s much more meaningful when we read it and then make a meal without the benefits of flour, butter, refined sugar, the giant box of kosher salt, and so on, to discuss how even “scratch” cooking is not too scratch thanks to our food supply chain.

Kerri: I agree with Jonathan. Ideally, I prefer limiting lectures and interspersing hands-on activities. In a class on the senses, I do some lecturing but I also have them taste foods blindly while holding their nose or drying their tongues to understand the effects of salvia or olfactory system. We use Prop/PTC taste strips to test if they are super or nontasters.

Sonia: I agree with Kerry and Jonathan. I like to create hands-on, collaborative, transdisciplinary and above all heterogeneous learning environments, where students can surprise themselves. Often we go out of the classroom. It is necessary to observe, but above all to talk to people.During the first sessions of design and design thinking, students are often disoriented and confused. I could also say that my students feel “lost” for 70% of the course. But this is a positive sign! Design methods require alternating divergent research phases with converging ones. I teach students to use very different ethnographic and research techniques. Sometimes even very “disruptive,” because I want to question many of their certainties about the world of food, but also about our ways of life and our real values as human beings. I love to see students finalize their discovery processes and start the solution design process, aware that what they design and create can produce a positive change in people’s lives (and therefore also in their food systems).

Did you receive any training around teaching/instruction in graduate school? What advice do you have for current graduate students who plan to stay in Higher Education, where many of us will have both teaching and research duties?

Kerri: I had a lot of experience in teaching before my current position at George Mason University. In my undergraduate degree, I worked as a teaching assistant leading labs. I had to learn how to organize students and explain what students were doing and learning. In graduate school I didn’t have training in teaching, but it also contained courses in educational theory, which has grounded my approach. My advice for current graduate students who plan to stay in higher education is to take advantage of teaching a course, serving as a teaching assistant or even workshops on teaching that exist at your institution. However, don’t do it at the expense of your research or publishing. Many institutions will hire faculty members with little teaching experience with a good research trajectory, but the reverse is often not true.

Jonathan: I do not have a lot of formal pedagogy training. I took a couple of education classes when I was doing my Ph.D. in food studies at NYU. However, these were more theoretical than practical in terms of classroom practice. I learned on the job and also through some great mentorship and faculty development programming, which never ends. I’m in the Drexel Teaching Academy this semester, which is a cohort through our Teaching and Learning Center. We take a class to improve our teaching and get “paid” in seed money to do SoTL projects or classroom technology. I’m constantly trying to learn and tweak my teaching without throwing out what works.

Sonia: My story is a little different. During my high school in Italy I studied to be a teacher, and I have been an educator for as long as I can remember. First I taught young children in primary schools and kindergartens, then I taught to teachers and professionals, as a professional trainer. My passion for higher education, teaching and learning techniques started when, more than 20 years ago, I wrote my MA thesis in Interaction Design on alternative educational processes for e-learning ( 20 years before Covid!). Then I designed a way to teach in prisons, and I won a scholarship to take graduate courses on “Adult Education” and “Integrating Technologies in the Secondary Curricula” in the US. I was in the US when I started teaching again: initially I started teaching my language in many Departments of Language and Humanities and then the Dean of the School of Art and Communication of the University where I was visiting professor asked me to teach “Introduction to design methods.” I loved to teach design. I stayed longer in the US and I tested a new pedagogical model, with the use of video editing, digital media, study abroad experiential learning,ect…. Once back in Italy, I had the opportunity to apply all the knowledge and teaching skills learned, in the COMPLEX world of Food Studies, by designing Gustolab and its alternative teaching method. It was a totally new world for everyone, which allowed me to experiment a lot and above all to do research (starting from my PhD) on the themes of food pedagogy, design and education for sustainability through food. For me, design is a way of transferring cultures and knowledge, so it is the perfect tool for teaching in food studies. In the Italian academic world the issue about the balance between research and teaching is a great point of discussion…. For example, to become a professor, a “teaching qualification” is required, but this is only provided after the evaluation of the publications produced. The number of years and courses taught are not counted for evaluation purposes. Surely this is a model to be improved.

How do you think that graduate programs could help to support their students who want training or experience in teaching and instruction?

Jonathan: Authentic opportunities to teach are key. I only got into teaching because I was a TA for a teacher who gave me the opportunity. A TA who just does grading or lab setup won’t get the development they need.

Kerri: The best way to learn is by doing. This is why education programs training teachers require student teaching experiences. Graduate programs could also offer training in different pedagogical approaches in teaching- experiential, didactic, dialogical, flipped classrooms, inquiry-based, game-based, etc. to understand various methods and the philosophies that underpin them.

Sonia: I totally agree. The best way to learn how to teach is to practice. It is also true that theoretical bases are needed, at least to understand that the teaching process must contain an exploration phase, an inspiration phase, a production phase followed by the sharing phase. There are techniques that can help every teacher to make their lessons engaging, but above all, as I used to say, co-constructions of knowledge. Only in this way our students are not mere “listeners,” but can become learning activators.

COVID-19 has changed – and continues to change – the way that we teach and learn. What is the biggest change you have had to make in your teaching and instruction since the pandemic began?

Kerri: Teaching Fundamentals of Cooking has been by far the most challenging and stressful to adapt. Cooking is something you have to do in practice in order to learn. Last spring when we shut down the campus I had to get special permission to use the teaching kitchen for a week to film cooking demonstrations and lessons for the rest of the semester. Students couldn’t get to the grocery stores. I went shopping for anyone that needed ingredients and had them either pick up in a parking lot or I delivered it to their door. It wasn’t ideal but we were all cooking the same thing and discussing what worked and didn’t online. This fall and spring, we moved to a hybrid model and I had a little more time to think about the delivery and assignments. I really like the outcome. It is something that I will continue even as we eventually move all in-person. I have altered assignments to be more experimental to understand the function of ingredients. They compare vegetables sauteed with salt and without, the tenderness of omelets cooked with butter and without, and the differences in the starch level of all purpose, starchy and waxy potatoes baked.

It has been challenging to move other classes online. I have tried to build in accountability to keep up with readings and classes and engagement between students. But I have had to eliminate many of the experiential activities that I would normally do in an in-person classroom setting. I am not sure how I feel about that if online teaching continues to rise overtime. There are certainly unique opportunities available. I know that Netta Davis at Boston University is doing some great work teaching sensory experiences online, but there are significant obstacles in making sure students have equipment, ingredients, food, etc. to be able to interact with what they are learning.

One thing that I knew but really understood through the pandemic is how much time it takes to develop a class. It takes almost the same amount of time to develop it into a different modularity, from in person to online or hybrid.

Jonathan: It’s been challenging. Our university wants to appeal to everyone and keep enrollment (fair enough!) so it’s been a bit something for everyone. I have students in person, via zoom, and some who watch recordings sometimes. It’s much more cumbersome than any single mode. I think having a background in the hospitality industry helps. We are trained to “roll with it” and adjust. Saying “I can’t accommodate” is not really an option.

Sonia: I faced this difficult period and I had to find solutions in the 2 different roles that I held in March 2020. When the pandemic arrived, I was still the director of an institute that had to manage food studies abroad courses (and was the first to have to address the repatriation of all students and the consequent forced quarantine). In addition I was also a university professor who had to completely redesign her design-based courses (collaborative and practical), to a “virtual” version.

In both cases, what was lacking most was the relationship with the territory, the possibility of going outside, seeing, observing, touching, experiencing everything in a synesthetic way. Doing ethnographic research became difficult. Above all, there was a lack of interaction with people. I compensated for this lack, alternating the use of videos with other forms of field-based research (obviously limited to domestic environments!) on the food systems of our daily life. I invited experts, and people to speak in my online lessons, and I reformatted the syllabi of all my courses (abroad and in Rome), so the student had the time to think about the issues of food sustainability, starting from themselves and above all from new scenarios that COVID was feeding.

Obviously the most impactful situation was for my study abroad students who saw their “dream of freedom and discovery” end overnight, to shut themselves up in their homes. Personally, I had already communicated my dismissal to Gustolab in February 2020, but I didn’t feel good about leaving the program in those difficult conditions. We therefore worked hard to transfer all academic activities in the digital version: using and discussing short videos made in Rome by previous students (peer to peer learning process), involving experts, doing remote cooking classes, reflecting together on food and Covid relationship, ect … A huge effort for all my staff. But we succeeded and before leaving my role as academic director of University of Illinois Urbana Champaign in Rome, I co-designed for them a “pandemic-style” program: a virtual journey on European sustainability through 4 cities (Vienna, Paris , Rome, Seville), a unique “virtual mobility” experience.

Recently, I joined the Future Food Institute team, where we addressed the problem of higher education during the pandemic, launching the “Climate and Food Shapers Bootcamp” Digital version … A real success! We recently won the International GoAbroad Innovation Award as the “ Best Innovative New Program.” This adventure continues today and is creating the foundations for a new way of studying abroad in the field of food and sustainable development. “Thanks” to COVID, we finally understood how interconnected we are .. and how much food is a key to understanding our local and global lives. This is my way of thinking and working, and it can be helpful to always create something new.

Do you anticipate any of these changes becoming a permanent part of your teaching and instruction?

Kerri: I will definitely continue to require experimental food labs at home. I need to do more assessment, but I think that students have learned more about the function of ingredients and foods. I have changed how I set up my learning platform, for George Mason University it is Blackboard. When the pandemic forced us to teach remotely, I quickly realized I had to change how I organized the course online. Instead of separate folders for readings and assignments, I embedded all necessary items into module folders, so students didn’t have to look in multiple places. Although I do have supplemental folders. It took work, but my course sites are a lot more intuitive. I will also continue to make weekly checklists for students. They help students keep on top of what they need to do.

Jonathan: Having students in different modalities has pushed me to be much more organized and deliberate in my communication. I can’t say something in lab and be sure the students working at home heard it. So everything is clearly laid out on our course site. I should have done it anyway but am more intentional about it.

Sonia: I totally agree with Jonathan. For me too it was a way to give “greater organization” to my activities and student work sessions. But also a way to understand what can be easily replaced by a video, a documentary, an online speech, and what is essential to do in class. Giving students independence in their learning process is important. We need to work more on the tools to be provided to them, so that they can create their own learning path, which must be increasingly critical and creative. And digital technologies, which have been our nightmare for the last year and a half, could, however, if used in a coordinated way in a hybrid model of education, improve students’ agency-based learning processes.

Have you found or made any resources that help with online or hybrid instruction?

Kerri: When the pandemic hit and through the past year, my university offered a ton of webinars and courses on online teaching, creating engaging synchronous sessions, using Zoom, etc. I attended a bunch of these. Some were not worth my time (ones created outside the university by Wiley) and some (ones made by our teaching and learning center) I will hold onto the skills and content I learned. One of the courses gave faculty members templates for Blackboard, activities, and assessments that I have gone back to.

Jonathan: The best program I’ve found for online teaching is Quality Matters. It is intense and time-consuming but using the quality matters rubric for your course design simply makes higher quality courses as the name suggests. It includes both pedagogical considerations (how does this learning activity align with my course objectives) and technical ones (how can I provide this reading in a way that will be accessible to a student using assistive technologies).

Sonia: I believe that the sharing tools that are available should be taught to all professors. I found design thinking tools extremely useful, as well as sharing whiteboards (Miro to mention one). But even to learn these, it takes time! It should become part of the skills to be acquired as a teacher. Often the students have become our “teachers” on these tools: and this too is an evolution and a co-construction of education.

We’d be happy to hear about anything else you’d like to discuss.

Jonathan: Thank you–pedagogy is such an important part of our work but we are often more excited to talk about our scholarship as a community. Please submit your teaching articles to Food, Culture and Society!

Kerri: This was great!

Sonia: It was SUPER nice to discuss these issues with you. Sometimes we tend to do, do, do … and never think about “why” we do it. University education is a little bit of that. Reflecting on “why” certain teaching methods are used rather than others is important. It is a form of respect for our students, who trust us for a small part of their life, to find direction and create the life they dream of.

I am happy to have been involved in this virtual panel with Kerri and Jonathan, whom I have known for many years now! I admire them as professionals, as educators, but above all as super people! Together we have seen growth and also changed the food studies in our universities