When did you first join ASFS? What prompted you to join, and what would you say is the benefit of joining back then as a graduate student?

I first joined ASFS in 2017 as a first year Ph.D. student. While I didn’t fully understand the purpose of associations when I joined, I knew food studies was going to be part of my larger research trajectory, so it seemed like a good idea. ASFS/AFVHS in Madison became my first conference experience and I became involved with the Graduate Association for Food Studies (GAFS) not long after that. One of the biggest benefits of membership was having dedicated space for peer-to-peer networking. I think many of us in food studies can feel siloed in our programs and joining ASFS, going to the conference, and getting involved all helped me build relationships outside of my department. I met some of my closest friends and collaborators at the 2018 GAFS Future of Food conference!

Your academic training is in History and American Studies – how do you bring this perspective to your work on food?

American Studies and History are both fields interested in narratives. Narratives can take different shapes and my research follows the stories told in, through, around, and with food. Temporally and spatially, my work looks to the past to help understand the conditions of the U.S. in the present and narratives being offered to people today. While food is my problematic, I am interested in food culture in the broadest sense, especially as it relates to other objects and humans including perfumes, advertisements, music videos, and celebrities. My subfields—critical food studies, material culture studies, cultural studies, sensory studies, feminist science and technology studies—offer me method and theory to more precisely articulate these relations, how they’re situated in broader narratives, and the stakes of those narratives. I see these fields as aligned because they all allow me to approach my problematic, food, from different modalities.

Could you tell us more about your dissertation titled Extracts, Essences, and Political Effects: How Vanilla Shapes American Life?

The dissertation-now-book project tracks vanilla’s various forms and shifting meanings in the United States. A central problem I take up is vanilla’s contemporary relationship with the ordinary, so much so that calling something “vanilla” often implies that it operates as a default. Beneath that surface layer, however, lies a complex and capacious cultural object. The project investigates multiple forms of vanilla—vanilla as an ingredient, flavoring, fragrance, and euphemism for race in the United States—to analyze how “plain vanilla” is produced and what lurks behind that veneer of supposed plainness.

You are currently the Abbott Lowell Cummings Postdoctoral Associate in American Material Culture at Boston University – for those just starting out on their graduate school journey, what does being a postdoc mean? Do you have any advice for those looking for postdoc positions?

A postdoc is a fixed term academic position that allow PhDs to continue their professional training. The conditions of postdocs vary a lot across fields, institutions, and programs. Some postdocs are one-year appointments where others may run for two- or three-years. Some postdocs are designed for fellows to further their research and make progress on their book manuscripts. Other postdocs are teaching or administrative positions. Often, the work of a postdoc falls across all three of these areas to different degrees. For example, I would characterize my postdoc as largely research focused although I teach one class per semester on material culture topics for Boston University’s American & New England Studies Program where I’m appointed.

For those looking for postdocs, I would recommend that you treat the search like any other competitive research fellowship or job application. If you have the time and wherewithal, take a look at the job market a year before you intend to be on it. Make note of postdoc programs, general deadlines, and common requirements to get a sense of what to expect. Many applications require similar materials—a cover letter, a research statement, a teaching statement, a writing sample, etc.—so developing drafts of those documents in advance could save you some effort when it comes to apply to a posting.

While at BU you’ve taught a class called “Material Culture: Thinking with American Pie” This sounds absolutely fascinating – please tell us more! Where did you get the idea? What does the class cover?

“Thinking with American Pie” has been a career highlight! The class serves as an introduction to material culture theory and methods for BU undergraduates. As a scholar I like grounding myself in concrete examples to work through theory and I liked the idea of having a common object that we could return to constantly as we read about and applied new concepts. I chose pie because it is an expansive kind of food that holds many variants but also because it seems ordinary and investigating it from so many perspectives helps make the familiar strange.

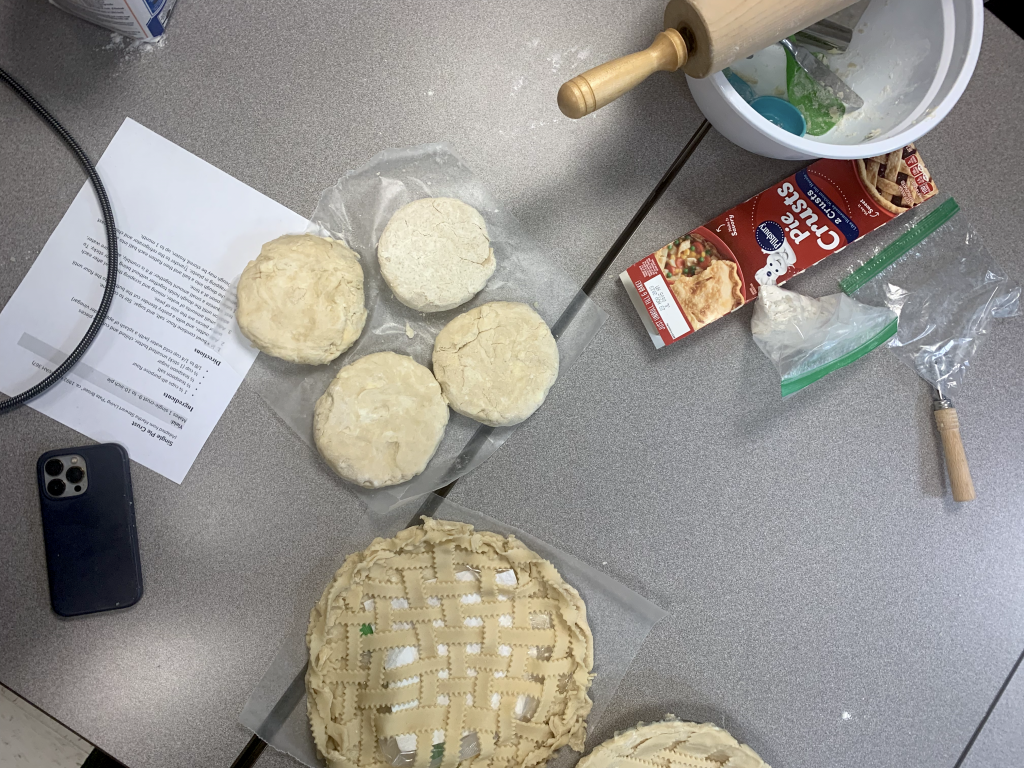

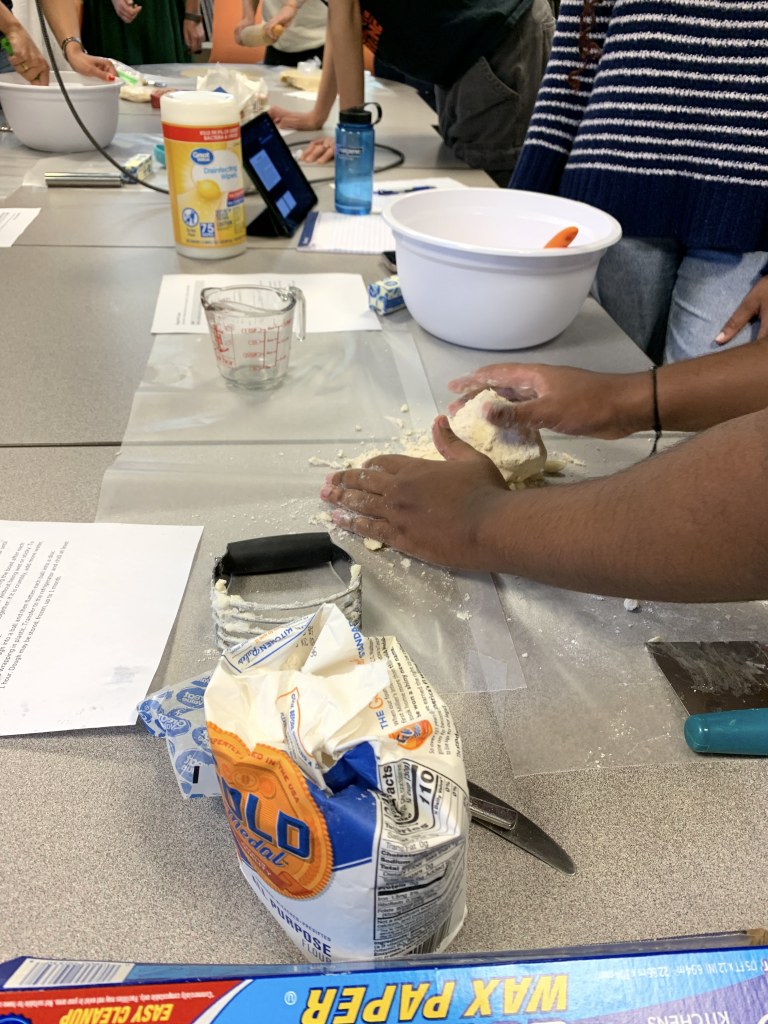

Over the course of the semester, we considered pie aesthetics, craft pie makers, and the politics of pieing another person. We talked about race, gender, and the power of national mythologies. To grapple with craft processes and embodied knowledges, we made pie dough in our seminar room. We ate pie together. We conducted research in BU’s cookbook library thanks to Megan Elias and the BU Gastronomy program. It was truly awesome. I couldn’t have had a better group of students and I’m so grateful to BU AMNESP for the opportunity and support to teach it.

More personally, I was introduced to the study of food as an undergraduate in a material culture seminar titled “Violent Cultures, Material Pleasures” offered by Christian Crouch at Bard College and the following year my undergraduate thesis took up apple pie to understand how and why it’s often used as a measuring stick for American-ness. In that way, the course is an homage to a formative moment in my scholarship.

Speaking of teaching, while at UNC Chapel Hill, you amassed quite the amount of teaching experience. Do you have advice about teaching and instruction for graduate students or postdocs who might just be starting out in the teaching realm?

I was in many classrooms at Carolina as a teaching assistant and instructor, and I am thankful for those experiences because I think teaching is something you learn over time. For graduate students, I would recommend paying attention to the teachers you admire. Whether they are a professor you’re assisting, a grad seminar instructor, or a pedagogy expert outright, there’s a lot to be learned through observation. I was lucky that I had mentors and classes with faculty at UNC who value teaching and purposefully modeled their pedagogy for graduate students. I am particularly indebted to Elizabeth Engelhardt, Kelly Alexander, and Jennifer Ho who all helped me come into myself as an instructor in ways big and small. For postdocs just getting into the classroom as instructor of record, be gentle with yourself. Teaching is hard. You don’t have to be a perfect teacher to be an effective teacher or a good teacher.

You have several public writing pieces and public scholarship – could you tell us more about writing public-facing work and why it’s important to you.

I love research and the depth of thought that characterizes academic writing. However, sometimes it’s frustrating that our work doesn’t reach more people. I see writing for public audiences as an opportunity to share knowledge beyond traditional academic venues, and cultivate my writing as a creative practice and craft.

I was interested in reaching wide publics before I started graduate school and was lucky that there was institutional support for public humanities work at UNC. I won a graduate fellowship that partnered me with the National Humanities Center thanks to a grant administered by Humanities for the Public Good, a UNC College of Arts & Science initiative funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. I worked with the National Humanities Center’s communications team to develop a podcast that featured the research of their research fellows past and present. After experimenting with different podcast structures and model, we created Nerds in the Woods where each episode explores a broad theme through interviews with the Center’s scholars about their research projects. I co-produced episodes on topics including Caribbean histories, reading modalities, Black power politics, design principles, and the intersection of humanities and AI technologies. It was such a treat to think beyond my fields and work collaboratively with a team at the Center.

Since then, I have been able to occasionally write for public-facing outlets and hope to do so more often. An article I co-wrote with my friend and collaborator Kelly Alexander was published with Aeon, which was an exciting milestone for me. Before her career as an anthropologist, Kelly worked at Saveur for many years and we had the best time trading drafts as we untangled the enduring status of French food in the United as invoked in many pieces of popular culture but epitomized in Kanye West’s much meme’d: “hurry up with my damn croissants!” In the process we both re-worked pieces that had previous academic lives and I learned tons as we worked with our editor to polish the piece.

It’s gotta be asked…. Chocolate, or vanilla?

This binary haunts me, but chocolate. I do, however, love a swirled soft serve cone.